What would you give — or give up — for a chance at true greatness?

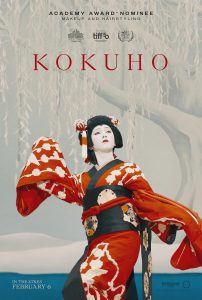

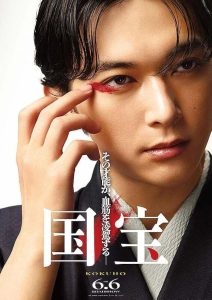

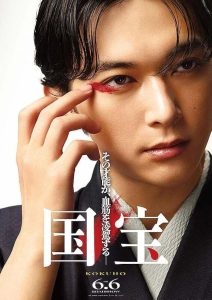

Kokuho (国宝, “National Treasure”) is a stunning glimpse into the heart of kabuki set against the backdrop of post-war economic boom. An epic tale of family, masculinity, craft, and friendship. Without spoiling it, the movie follows Tachibana Kikuo, the orphaned son of a Yakuza boss who is taken into the care of national kabuki treasure Hanjiro Hanai II. Hanjiro is currently raising his own son Shunsuke to become his successor and inherit the title of Hanjiro Hanai III. Both boys come to take on the roles of onnagata, performers who play the female roles in kabuki, which contrasts sharply with the hyper-machismo of the Yakuza world that Kikuo knew beforehand. The boys are trained in unison, leading to a beautiful rivalry full of professional and emotional passion as well as heartbreak, and ultimately, triumph.

The movie spans decades, from the early sixties straight through to a finale in 2014. I am not here to summarise or spoil it, so I am not going to delve into the plot, but that timeframe encompasses so much character development, both positive and negative. We see Kikuo and Shunsuke’s lives interwoven as they train together, rise to stardom together, let bitter rivalries and the public’s fickle attention get the better of them. We see them at their highest, and at their lowest, and at all the poignant messes in between as their careers ebb and flow, and as they drift and out of each others’ lives. Kokuho is not what I would consider an uplifting movie, but it has moments of great optimism and hope, and a pure and devoted heart.

I admit I went into the movie biased for two reasons; first, and most obvious, is the wardrobe and set design. This movie is absolute eye-candy for anyone interested in kimono and traditional Japanese arts. The second — and far more vapid — reason is that Watanabe Ken plays the veteran kabuki star, father, and mentor Hanjiro. I could watch that man read the phone book and be happy with my life choices, if I’m being honest.

Kokuho is a visual masterpiece, a lush love letter to a venerated art form. The story unfolds in a sharp contrast of dramatic, gut-wrenching action and quiet, meditative moments that embody the Japanese concept of ma (間), a sort of purposeful void, pause, or empty moment that helps to emphasise the action or space surrounding it. Ma is often used in traditional theatre, both noh and kabuki, and I have no doubt the similar use of pauses, silences, and visual empty or liminal spaces was absolutely intentional. However, it can make things hard to follow if you are unfamiliar with it; jumps in scene, location, or emotional tone may end up feeling disjointed or even badly edited to viewers without that frame of reference. The lives of the actors are interwoven deftly with stage performances, which help to underscore the reflected themes and emotions happening in both, but again, this may prove distracting or confusing for some viewers, especially those coming into this with little to no knowledge of kabuki.

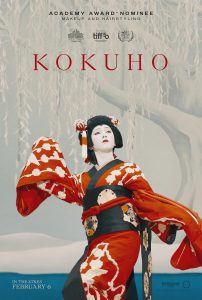

It may be due to this that Kokuho was not nominated for a best foreign film Academy Award, which is a travesty in my opinion. I haven’t seen any of the films that did get nominated but I stand stubbornly by my statement, because this is my blog and I can. It was nominated for Best Makeup and Hairstyling, which I absolutely understand. Not just for the traditional oshiroi and wigs, but for the incredibly natural aging that happens over the course of the film. It’s impossible to tell what ages the actors actually are, and if they were aged down or up. I do hope we get to see the team in kimono (and maybe even nihongami) on red carpets during awards season, but I don’t have my hopes up.

It may be due to this that Kokuho was not nominated for a best foreign film Academy Award, which is a travesty in my opinion. I haven’t seen any of the films that did get nominated but I stand stubbornly by my statement, because this is my blog and I can. It was nominated for Best Makeup and Hairstyling, which I absolutely understand. Not just for the traditional oshiroi and wigs, but for the incredibly natural aging that happens over the course of the film. It’s impossible to tell what ages the actors actually are, and if they were aged down or up. I do hope we get to see the team in kimono (and maybe even nihongami) on red carpets during awards season, but I don’t have my hopes up.

There’s a reason Kokuho has become the highest-grossing live-action film in Japanese history. It’s more than a “foreign film” at this point, it’s a global phenomenon. And not without due cause; it is a feat of both visual and emotional storytelling. It’s rare that I sit through an entire movie without getting up at least a couple of times to pee or stretch my legs — let alone a movie with a three-hour run time. During my first watch, I somehow managed to stay put for the whole thing (minus one quick washroom break), and at no point did I find myself wondering how much was left. The second watch-through was much longer and more fragmented over the course of several days, as I paused regularly to take notes and capture images.

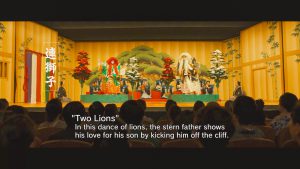

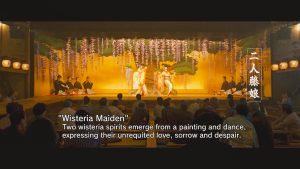

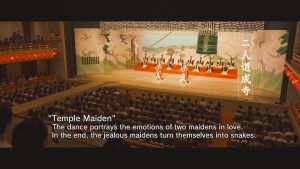

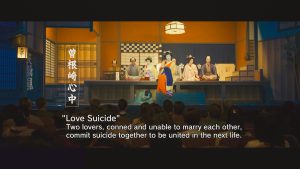

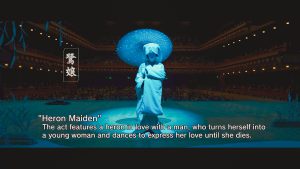

One repeated device in the movie that I really appreciated, as someone not terribly familiar with kabuki, was these cards at the beginning of every major dance sequence. It helped give context to each dance, which is vitally important since, as I mentioned earlier, the themes and emotions conveyed in the dances often mirror what’s happening off-stage in some way.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Kimono Tsuki review if I didn’t talk about the kimono, now would it? The thing that started my love letter to the Japanese arts, and continues to be my primary obsession. The stage costumes, obviously, are all lush, gorgeous, and deftly handled. The costumes in kabuki tend to be relatively standardized and help to identify the characters and archetypes being performed, so it’s no surprise that a movie that is such a passionate and thorough love letter to the art form went all-in with the costuming. What really caught my attention, kimono-wise, was how well the non-costume outfits were coordinated, and how well they telegraphed pertinent details such as age, status, time of year, and yes, decade. From the rough meisen day-wear of the 60s to the subdued silk houmongi of the 80s, they really ensured that the style, colours, and patterns of each kimono accurately reflected what situation and timeframe of the movie we were in. Considering the attention to detail in the rest of the movie, I should not have been surprised by this, but it was still a lovely thing to see.

Speaking of “lovely things to see”; when I say it was nearly impossible to keep my screenshotting to a minimum here, you need to believe me. Since Kokuho is over three hours long and nearly every scene is visually stunning, I had to be selective. I also had to skip over large chunks to avoid spoilers. And I still ended up with all these breathtaking images I had to share with you.

My only real “complaint” (such as it is) about the movie is that there are so few women in it, and they’re so one-dimensional that they may as well all be the same character. However, this is the story about two men, their friendship, and their journeys, so nearly all the secondary characters are equally undeveloped. Kabuki has historically been a male-only field — hence the need for onnagata — so it makes sense that the female characters are basically set dressing or accessories. It is simply something to keep in mind if that sort of representation is important to you.

Kokuho will be receiving a wide English-subtitled North American theatrical release this coming Friday, February 20th, and will hopefully be available on streaming and blu-ray later this spring. If you are creative

Kokuho will be receiving a wide English-subtitled North American theatrical release this coming Friday, February 20th, and will hopefully be available on streaming and blu-ray later this spring. If you are creative at sailing the seas of the internet, there are ways to find it currently (which is how I was able to get screenshots) but I urge you to show your love and support for this fantastic movie by seeing it on the big screen. The visuals alone will be worth it.

Kokuho on IMdb

Kokuho on Wikipedia

Bebe Taian

Bebe Taian CHOKO Blog

CHOKO Blog Gion Kobu

Gion Kobu