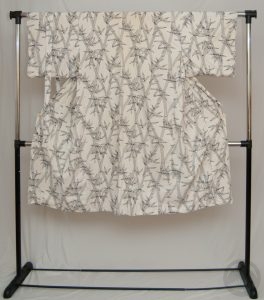

Fudangi, 不断着, home wear/casual clothes/ordinary dress

That’s a delightfully vague definition. Much like the infernal “office casual” it’s a term that leaves a lot of room for interpretation. So what exactly is fudangi? The general consensus for kitsuke is that it comprises anything from wool or cotton kimono that you’d wear around the house to komon and obi without metallic accents that you’d wear to run errands or meet up with friends for lunch. Often it’s much looser and more relaxed when it comes to the rules, but you still want to avoid anything overly formal. Obi should be hanhaba or casual nagoya, obijime should be thin, fancier textiles like shibori or yuzen-dyed silk should be used sparingly if at all. Think of rough-woven and rustic textiles like wool, meisen weave, etc. Fun accessories like haneri and obidome are always a good way to inject some personality in.

To give a better idea, I’ve collected some of my favourite coordinations from last year, where I made an effort to put together an outfit that exemplified fudangi at least once per month. As you can see, there’s plenty of room for variation, all while staying relaxed and comfortable.

As much as I love really gorgeous formal furisode and kurotomesode, there’s a lot to be said for casual, cool, comfortable outfits like these.

Bebe Taian

Bebe Taian CHOKO Blog

CHOKO Blog Gion Kobu

Gion Kobu