I certainly chose a fantastic time to leave California and head back to Montreal, didn’t I? The weather in this entire half of the continent is certainly something else right now. I am so thankful I work from home these days, and that my folks are retired and don’t have to leave the house in this disaster.

That being said; what better time to curl up with a fantastic book and a warm cup of genmaicha and let your mind drift to a different country, a different climate, a different time, a different world? I’ve been meaning to start doing fiction book reviews here to go along with the more kimono-specific non-fiction, and it looks like the universe just gave me the nudge I needed.

That being said; what better time to curl up with a fantastic book and a warm cup of genmaicha and let your mind drift to a different country, a different climate, a different time, a different world? I’ve been meaning to start doing fiction book reviews here to go along with the more kimono-specific non-fiction, and it looks like the universe just gave me the nudge I needed.

This first post will include a couple of novellas and shorter novels all in one entry, and if you enjoy it I will work on writing longer ones about individual books in the future! I also don’t want to give too much away, as these should all be read somewhat “blind” to truly appreciate them.

As always links to purchase the books, where available, will be included. And if you’re wondering why I’ve used stock images for the covers, it’s that several of the physical copies for these stayed behind in California and the rest are on my e-reader.

The Samurai’s Garden, by Gail Tsukiyama

The Samurai’s Garden, by Gail Tsukiyama

Okay, right off the bat, parts of this book are definitely less relaxing than others. Set against a backdrop of tuberculosis, racial tension, and a dawning war, this is the story of Stephen, a young Chinese man sent to rest and recuperate on his family’s property in Japan on the cusp of WWII.

Without giving too much away, he forms a bond with the gardener and learns so much more than just gardening. The stories of past and present both unfold and open up slowly but steadily, much like Stephen himself.

This one is a classic for a reason, and if you have not had the opportunity to read it (or anything else by Gail Tsukiyama), now is the time. It should also be mentioned that Tsukiyama is American of Japanese descent and this is the only book on the list that was written originally in English.

Read The Samurai’s Garden on Amazon | Abebooks | Kobo

Kitchen, by Banana Yoshimoto

Kitchen, by Banana Yoshimoto

What do love, loss, food, and gender expression have in common? They’re all things that are very important to me, and they all play roles in this next book.

I cannot express how much I love Kitchen. I’m a fan of all of Yoshimoto’s work but this little diamond in particular will always have a special place in my heart. So much so that I’ve replaced two physical copies and am on my third, and I have a digital copy as a backup. I picked up my first copy in the early nineties and have utterly lost track of how many times I’ve re-read it since then. Yes, I’m old. Shush.

The book is typically printed as two novellas, the longer eponymous one and a shorter one entitled Moonlight Shadow. Both are stories of people learning to cope with a new status quo after losing loved ones and both contain secondary characters who, to different extents, have begun experimenting with gender presentation or cross-dressing as coping mechanisms. Kitchen focuses much more on the role of food as ersatz therapy, but Moonlight Shadow also has a tea thermos play a pivotal role. At their hearts though, they’re both about beautifully imperfect people learning how to move forward after painful losses.

Including stories that revolve around death may be an interesting choice for “cozy” books, but it’s handled with such a gentle, soothing touch and hopeful notes in both cases that it’s an incredibly cathartic and comforting read. Especially if you’re dealing with similar feelings in your own personal life.

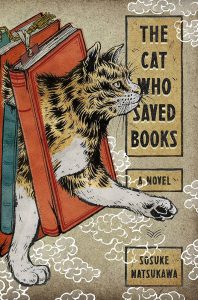

The Cat Who Saved Books, by Sosuke Natsukawa

The Cat Who Saved Books, by Sosuke Natsukawa

Did I initially pick up The Cat Who Saved Books because I suspected the cover art was by one of my favourite artists, Yuko Shimizu (no, not she of Hello Kitty fame – the other, cooler Yuko Shimizu)? Yes. Yes I did. Was I correct about the cover art? Also yes. Have I read it several times since then because I love it so much? A third, resounding yes.

This is one of the coziest books I’ve read recently, and is often cited as an emblematic example of iyashikei, 癒し系 or “healing” literature. In the past few extraordinarily stressful decades, iyashikei has emerged as its own subset of Japanese media, primarily anime and manga but extending to fiction and live-action.

The Cat Who Saved Books falls into the genre of magical realism and fantasy, so if that’s not your bag you might want to skip it. But if you love books, and if a nerdy teenager and his talking cat who run through mazes and puzzles to save forgotten books from irresponsible owners sounds appealing to you, read on! Rintaro Natsuki inherits a bookshop from his grandfather and is initially going to close the shop, until Tiger the shop cat starts talking to him. They set off on adventure together to protect the written word. This book is, well, a love letter to books.

There is also a sequel, The Cat Who Saved The Library, which I have not had the chance to pick up yet but it’s also on my list! I would also love to see this made into an anime or movie.

The Kamogawa Food Detectives, by Hisashi Kashiwai

The Kamogawa Food Detectives, by Hisashi Kashiwai

What if someone could recreate a dish from your memory, one that could transport you back to a place, a person, or a time long since past? Set in a little restaurant off the beaten path in Kyoto, this is the story of a father and daughter who help heal people in small doses, one bite at a time. More like a series of interconnected stories, each one focusing on a specific guest, recipe, and memory. This also makes it great bedtime reading, as you don’t feel compelled to stay up all night to finish the book, when you can finish one part at a time.

The Kamogawa Food Detectives will make you feel wistful, happy, peaceful, and incredibly hungry all at once.

This is the first book in a trilogy, and the other two books are very near to the top of my reading pile. While I can only speak for the first one, I have linked to the other two below as well.

The Kamogawa Food Detectives on Amazon | Abebooks | Kobo

The Restaurant of Lost Recipes on Amazon | Abebooks | Kobo

Menu of Happiness on Amazon | Abebooks | Kobo

I hope if you decide to read any of the above books, I hope you find them as lovely and soul-enriching as I did. I have more similar books to read soon, including What You Are Looking For Is in the Library by Michiko Aoyama, The Convenience Store by the Sea by Sonoko Machida, and Days at the Morisaki Bookshop by Satoshi Yagisawa. If you have any other suggestions of other cozy books I should read and review, or any other novels to check out, let me know in the comments!

I purchased this item myself and chose to review it.This post contains affiliate link(s). If you choose to purchase, I receive a small rebate or commission which goes to the continued maintenance of this site.

Bebe Taian

Bebe Taian CHOKO Blog

CHOKO Blog Gion Kobu

Gion Kobu